Category

Helpful Links

- Home > Latest News > ‘A Shadow the Length of a Lifetime’: A Survivor’s Story

‘Child Sexual Abuse Casts a Shadow the Length of a Lifetime’: A Survivor’s Story

TRIGGER WARNING: The following story contains discussion of child sexual abuse and suicide. If you need support, please reach out to Bravehearts’ Information and Support Line (8:30am – 4:30pm, Monday to Friday) on 1800 272 831 or Lifeline (24/7) on 13 11 14.

My story begins in 1968, a year that will be remembered historically for many notable events including:

– The assassinations of both Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy;

– Boeing introduced it’s 747;

– Apollo 8 orbited the moon; and

– The Beatles ‘Hey Jude’ went to number one.

I will remember 1968 as the year which changed my life forever. I was a fifteen year old boy with both a happy family and school environment. Wednesday 17 July was my life changer. I was in grade ten at a very good public school, grade ten was the make or break year when academic futures were determined.

I had my sights set on studying law at university. It was lunchtime, I was talking to my mate Robert when I was confronted by the principal and told in an aggressive tone to go to his office. The reason being, I was wearing black socks, I did not think too much of this, nor did I have any idea my life was about to change forever.

He was an irascible unpleasant man, and a chain smoker. Little did we know that a far darker evil lurked within. As I waited on the verandah of the school’s admin wing I noticed his secretary was packing up to leave, to the teacher’s lounge for lunch I presumed. When he appeared, he summoned me into his office with a peremptory wave of his hand. Once I was behind locked doors the assault began, verbally at first, I was berated for the horrific offence of wearing black socks when the school dress code called for ‘college grey’. But, then things really escalated.

He reached for one of his many canes, told me to drop my trousers and underwear, I winced but complied, I expected to be caned on the backside, which was cruel enough. But he did something far worse, something far beyond my life experience and even farther beyond my worst imagination. I froze in shock, terror and incomprehension.

Once he had finished sexually assaulting me, the threats immediately followed – expulsion from school, public humiliation, the ruination of my life if ever I breathed a word to anyone. As if my life hadn’t been ruined already. With one foul swoop my abuser sent me cascading down into my own personal hell. My mind was consumed by a feverish swirl of thoughts and questions.

Why did this happen?

What type of person was he to commit this vile criminal act?

Would it happen again?

Who would I tell?

Would I need to see a doctor?

Was I the guilty person?

If I told my parents would I be believed?

I think about that moment every day, it never leaves me. I had no doubt how my father would react if he ever learned what happened to his son. He would do the right thing morally – and the wrong thing legally by exacting some old-fashioned frontier justice.

‘If I did tell what had happened to me – would I be believed? I was a fifteen year-old kid, while my abuser was a respected educational leader and a prominent figure in local society.’

If I did tell what had happened to me – would I be believed? I was a fifteen year-old kid, while my abuser was a respected educational leader and a prominent figure in local society. At the end of the day, it would be my word against his, and I couldn’t get it out of my mind that his daughter was in grade twelve at the same school. Wasn’t she another innocent in all of this? I didn’t even think about going to the police, remember this was a time when such matters were completely taboo. They were never discussed – not in the media and certainly not in polite society.

The idea that he had done something criminal didn’t occur to me, I dealt with the trauma through denial and repression. I convinced myself that nothing had happened, even though he assaulted me twice again over the months that followed. His third attempt only failed due to interruption. I’ve arrived at the conclusion that his secretary knew exactly what was going on. Her downcast eyes, her deadpan expression as she slipped away on some pretext or other whenever I attended his office. These were clear giveaways that she knew and yet did nothing. That she valued a steady job over the well-being of the children in her charge was a betrayal by omission.

At this point in my life, I faced a choice, the same momentous choice that is forced upon all child victims of sexual abuse. Wracked by insufferable pain inflicted by unimaginable trauma, too many victims risk solace from suffering through alcohol, drugs or other destructive behaviours. For some reason, because of an internal instinct for self-preservation, I chose a different path. For some reason I chose to become the master of my trauma, rather than let the trauma master me. I discovered that rational strategy could become a very powerful tool for self-preservation and life success. I waited and plotted my escape.

I wagged school, secure in the knowledge that he would never dare challenge me for fear of exposure. I spent many hours at a park along the Brisbane River, often with my mate Robert. I never told him or anyone else what happened to me. I didn’t have to. To this day I’m convinced he knew because something similar had happened to him, his sad eyes said it all. Towards the end of that terrible year, I told my parents that my current school couldn’t offer me the choice of subjects I needed to qualify for university studies in law. This was complete fiction; my parents were wonderful people who believed in me and thus believed me. I told them I could complete years eleven and twelve at the same school attended by my cousins. I told them there would be no extra costs except for a slight change in school uniform, the deal was sealed, I was free.

To celebrate my liberation, I burned those parts of my former uniform that I wouldn’t need. Robert and I said our goodbyes and promised to stay in touch. I still have fond memories of our times together, there was one experience that comes to mind whenever I see a preview on TV for the classic Rob Reiner movie Stand by Me.

Robert and I were wagging school, we decided to cross a rail bridge spanning the Brisbane River when we were jolted out of our reverie by a series of loud blasts that sounded like a foghorn. We turned around and saw a train approaching at speed and like in the movie we were trapped midway across the bridge. We jumped down into the river, we survived no worse for wear, but our books and bags were never the same.

My father died in 1970 without ever learning what happened to me and while part of me was sad that I never brought him into the circle of my terrible secret, I also know that I’d done the right thing. Not only did I spare him the searing pain that would have been the consequence of knowing, but I also forestalled a whole set of legal problems that surely would have ensued. I have no doubt my father would have gone medieval on him, to the point my righteous father would have ended up in prison for sending him to hospital, if not the morgue. My father’s death left my mother in a not-so-good financial position. My five siblings pitched in, but they had their own lives to lead.

I left school to support her, I joined the Queensland Public Service and completed my high school studies by attending night classes. The life of a bureaucrat was not the future I wanted and after a year or so I moved on to the world of insurance. I never qualified as a lawyer, much less studied at university. I nonetheless had a very successful business career climbing through the ranks to a senior executive role in a global corporation. I accomplished this in part by being an absolute workaholic. I routinely worked fourteen-hour days over six-day weeks. In retrospect, I recognised this was my way of sublimating my trauma. Rather than alcohol or drugs, I chose to drown myself in work, a more constructive choice in many ways.

In many ways, it was a band-aid solution to a gaping wound that could not heal. Each day I asked the cosmic question of why this happened to me. And each day, I silently berated myself wondering how many other innocents suffered at his hands because of my self-imposed silence. I would rejoice when reports of pedophiles being caught and punished would appear in the newspapers and TV news. However, I remained desperate to keep my secret. I was ever vigilant where my five children were concerned. They would tell you I was hyper-vigilant.

‘I was wracked by guilt over possible injury to other children I felt I had enabled by letting him get away with his crimes.’

At the same time, I was wracked by guilt over possible injury to other children I felt I had enabled by letting him get away with his crimes. It was all terribly corrosive to my psyche and soul. In 2009, the buttress holding up my facade of my normality began to crumble and give way. I succumbed to a debilitating anxiety disorder that forced me into medical retirement. Throughout my life and career, I had managed to hold at bay the demons of my trauma, but I had reached a point where I just couldn’t do it anymore. I grudgingly agreed to see a psychiatrist.

But, in my heart of hearts, I was like one of those alcoholics who spends his time in rehab counting the 28 days until his next drink. I didn’t, I couldn’t tell anyone about my trauma, not even my psychiatrist – what was I to do? My old coping strategy was no longer operative because I was now retired. I had no work in which to bury myself, so I buried myself in a different way, I became a recluse, I shut out as much of the world as I could, avoiding people and family events on the lamest of excuses. I wouldn’t leave the house for days at a time.

My wife and children were shattered, this was the price of hiding my shame, it was my personal tragedy. Those that I loved ended up paying the price. Like the folktale of the Dutch boy trying to stop the leaks in the dyke with his fingers, it could only go on for so long. And on 19 June 2014 I ran out of fingers. I had another emotional breakdown, this one total. A few days earlier my wife went to Sydney with her sister. In her absence I fell completely to pieces, my defensive wall was breached and I was inundated by a tidal wave of pain and guilt.

Better to end it, I thought, so at 2:00am I drove to the rail crossing at Northgate. I sat there trying to work up the nerve to do the deed. Then suddenly, images of my much-adored grandchildren began to flash through my mind. It suddenly dawned on me that there was nothing courageous about what I was planning to do. I would disappear in a grinding crash of metal and flesh, leaving my wife and family to pick up the pieces literally and emotionally. I suddenly understood I was contemplating an act that would inflict grave harm on those I loved most.

I drove back to my empty home and did the first truly courageous thing I had done in quite a while; I asked for help. I phoned my sister, she contacted my brother who immediately came over to keep me company and keep me safe. My wife hopped on the first available plane. On doctors’ advice, I admitted myself to Belmont Private Hospital. This in itself was an experience, the likes of which I had never known. When they confiscate your shoelaces and razor, you know things are getting serious.

‘…she brought me to understand that I was the victim who had no cause for shame or guilt.’

I was in a state of internal panic, knowing my secret was about to come out, yet dreading the consequences of that unavoidable reality. Remember in my mind I was the weakling who failed to protect other children by keeping his crimes to myself. I was fortunate to be in the care of a consummate professional Dr. Robyn Cross. I had sessions with her every day, and she brought me to understand that I was the victim who had no cause for shame or guilt. She made me see that I was just an innocent child who had been defiled and abused by an evil man. She told me in all her years of psychiatric practice, she had never known a sexual abuse survivor who had kept this secret so long and so well.

I was prescribed heavy doses of medication, and in the early stages, I have no recollection of the many times my family came to visit. All in all, I was hospitalized at Belmont for a total of seven weeks and over that period Dr. Cross and I, together, managed to cast aside the terrible weight I had borne all those years. I still retain a significant measure of regret for not exposing him and his crimes, that is something I have to live with. As I healed, I asked my wife to tell our family and friends what happened to me, I wanted my abuse to be told.

Upon my discharge from Belmont, I set about fulfilling two promises I had made myself while in treatment:

- Report him to the police, and

- Tell my story to The Royal Commission

My formal statement to the Queensland Police generated an enquiry that found he died in 2002. I was sad that in death he escaped punishment for his crimes, but, at the same time, I was pleased he wouldn’t be around to abuse other children. My experience with The Royal Commission was extremely positive. I was treated with tremendous compassion and respect. I learned there were 13,000 other Queenslanders who had come forward with similar stories of abuse. I was granted a personal interview. The Commissioner who spoke with me was the recently retired and respected Queensland Police Commissioner Bob Atkinson. This interview enabled me to enter my account into the public record.

I then set about trying to reconnect with my childhood friend Robert. I managed to speak with his sister who told me Robert took his own life at age 26. He left no note or clues as to why, but I believe he was another victim. I think about Robert often and will treasure our friendship forever. After my interview with The Royal Commission, I instinctively knew that my next life challenge must be one that would lift me up both literally and spiritually, a physical and mental challenge that he, the criminal could never accomplish.

After several weeks of research, I found what I sought at the summit of Africa’s highest mountain – Mt. Kilimanjaro soaring just shy of 6,000 metres above the Serengeti in Tanzania. I knew this was not going to be an easy challenge, so I began to prepare. Four to five hours of strength and endurance training every day for eight months and the important selection of gear and clothing. In July 2015 I joined a group of seven climbers, four guides and twenty nine porters for the ten day climb.

Each step was hard, I persevered and at 10:30 at night on 16 July, I left Barrifu camp with my guide Justin to make the final attempt to the summit.

It was a nine hour slog and at 7:10 on the morning of 17 July, 2015 there I was – on ‘The Roof of Africa’. It was exactly forty-seven years to the day since his first assault. The temperature was minus 20 Celsius, but neither cold or exhaustion could dampen my exhilaration. Overcome with emotion I said to Justin “I’ve beaten this bastard, he would not have been able to this”.

Justin looked back at me with incomprehension, but that didn’t matter, it was enough I knew. Standing on the summit of Kilimanjaro gave me the feeling that I was the only person on Earth, I felt safe in my serene solitude. After taking photos, we began our descent, you cannot stick around too long at that altitude, they call it the ‘death zone’.

Upon our return to base camp, we were greeted with hot food and drink and then our porters did something that I’ll never forget. They began to chant “Simba…”

“Simba…Simba.”

I looked at Justin for an explanation, he smiled, “Simba means lion in Swahili, they are saying you have the heart of a lion.”

To me their chant confirmed the reality I had truly beaten him, that when I touched ‘Roof of Africa’ at the apex of Kilimanjaro, I was seizing control of my destiny.

‘What motivated me to keep going, to keep putting one foot in front of the other despite the cold and fatigue, was the suffering of any child, anywhere, at any time who has endured sexual abuse.’

Whilst I was certainly pleased about my personal achievement in climbing Kilimanjaro, it really was an exercise about so much more than one individual. What motivated me to keep going, to keep putting one foot in front of the other despite the cold and fatigue, was the suffering of any child, anywhere, at any time who has endured sexual abuse. I was doing this much more for them as for me, and for them I simply had to reach the top.

For my sake and for theirs I had more mountains to climb. My next ascent was Mt. Aconcagua in the Argentinian Andes. Over a twenty day climb I reached within 300 metres of the summit before bad weather forced my group to retreat. No matter, 6,700 of Aconcagua’s 7,000 metres was good enough for me because it was far beyond anything he might ever accomplish on his best days. When I returned home, some of my fellow climbers suggested we take another crack at Aconcagua to finish off the last 300 metres. I smiled, my response was that it wasn’t the 300 metres that worried me, it was the 6,700 metres to get to them.

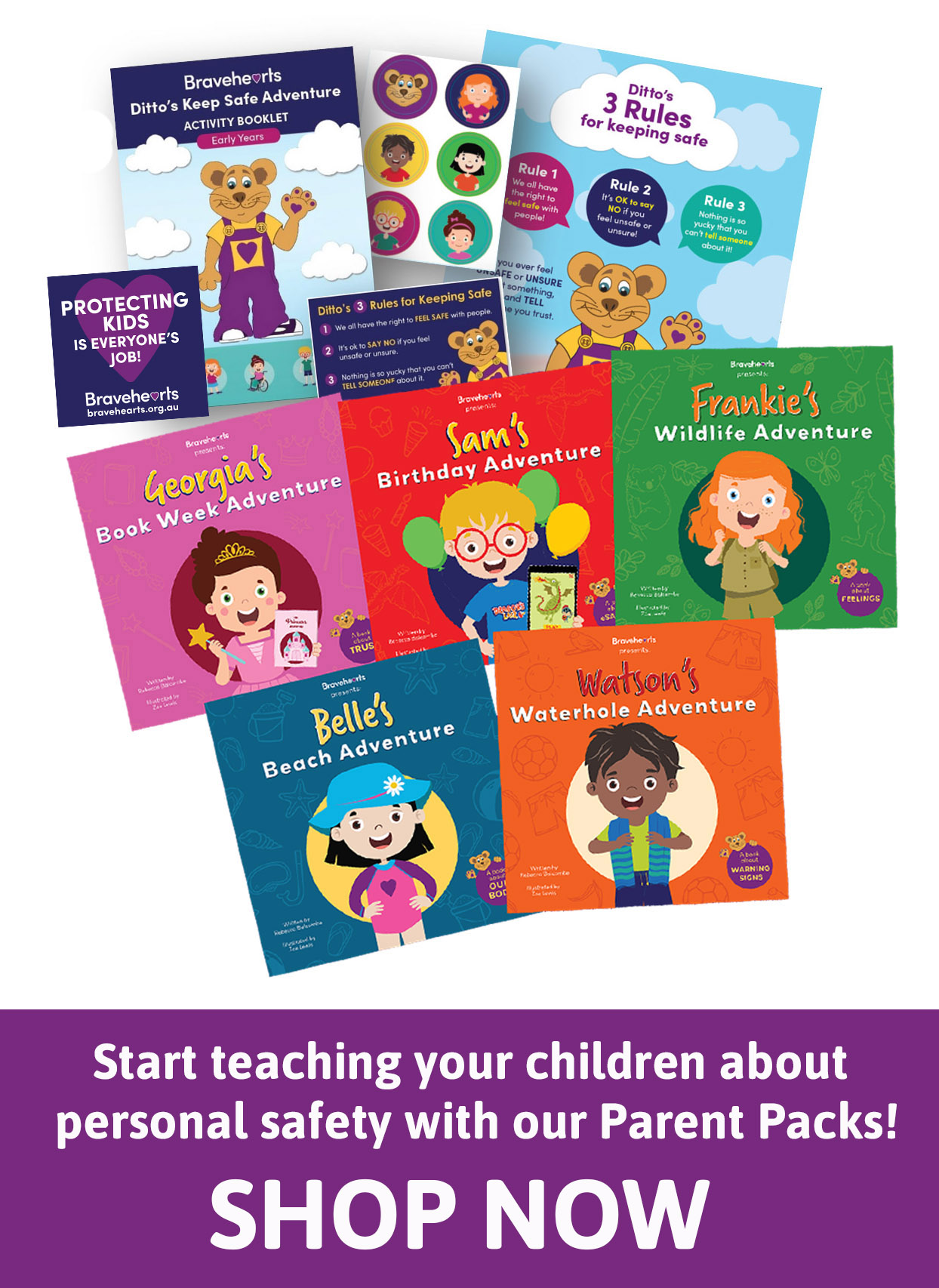

I confess my lovely wife has been less than enthusiastic about my mountaineering endeavours because of the dangers involved. However, she still supports me for which I’m very grateful. I’ve promised her my next climb, yet to be decided, will be my last, and after that my climbing gear will be donated. I’ve raised funds for Bravehearts the not-for-profit advocacy group, they have become a very important part of my life. They have been instrumental in lobbying the various State Governments to repeal legislation governing statutes of limitations on liability relating to sexual abuse.

Because of this, I was able to file a suit against the education authority that should have protected me, but did not. My action was successful, I received compensation, but I had to sign a Confidentiality Agreement In return, hence my inability to name the guilty party.

‘It gave me the chance to tell people the horrors of child sexual abuse, the impact it has on you and your family and how it changes your life (if you survive).’

At the settlement conference, I was afforded the opportunity to read out an Impact Statement (as I would have struggled to do so, my Barrister read it out). It gave me the chance to tell people the horrors of child sexual abuse, the impact it has on you and your family and how it changes your life, if you survive.

This was the Statement:

you are in shock;

you feel dirty;

you feel violated;

I was suffocated with fear;

you’ve been scarred for life;

you become self-embarrassed;

you are physically and mentally injured but can’t seek medical help because the doctors will know what happened to you;

you feel trust and protection are just made-up words:

you question yourself over and over again as to why the rapes occurred;

you start to believe you are the guilty person;

you can’t tell anyone because you worry about being called a liar;

you do not want to embarrass your family;

you go into survival mode which dominates your life;

you hope everyday that something will happen to the criminal;

I lived two lives, my inner life which was my secret, and my outer life, where I needed to be strong to get me through every minute, hour and year of my life;

my ambition to study law was taken away from me;

I lived in permanent fear my secret would come out;

I’ve never shown my children where I went to school;

I’ve never had a physical for prostate nor have I had a colonoscopy, I never will;

remembering the noises and images of being abused, and the smell of cigarettes on him;

remembering the look on his secretary’s face;

having to continually make excuses to avoid people;

going to places for long periods so I could be alone;

never enjoying happy events when I should have been happy;

suffering from constant lack of sleep;

taking heavy medications which wreaked havoc on my system;

the constant feeling of melancholy and loneliness;

remembering every word of his threats;

having to relive every moment when being assessed by psychiatrists;

his way out was by dying, I’m still living with the memories of what he did to me fifty years ago.

When the conference finished, I said to my wife, “All that happened here today was that fifty years of my life trauma was kicked around for a dollar amount.”

However, the settlement represented another win for every child who has been sexually abused. This was never about money, a stack of $100 notes higher than Kilimanjaro would not, could not heal the trauma of rape. I never kept one cent from the settlement, the money was used to support my children’s mortgages.

‘You can spend your life trying to forget a few minutes of your childhood.’

Child sexual abuse casts a shadow the length of a lifetime. You can spend your life trying to forget a few minutes of your childhood. The life-changing obstacles that I’ve faced are the reason for my self-motivation, it’s my motivation to change the outcome of my life because no one else can control it anymore. It allows me to focus on things which are important to accomplish. These life-changing situations allow me to demonstrate who I am and what I’m capable of achieving.

I still have anxiety issues and flashbacks, I always will. I’ve been back to Belmont a couple of times when I needed a little help, I no longer take medication, and I’m very careful of news stories concerning pedophilia because of the thoughts it can trigger. I’ve moved on, however, I will never forget what happened to me in 1968, I survived. The Royal Commission into Institutional Child Sexual Abuse has ended, I only hope their findings and recommendations will help to ensure important and lasting changes are made so that this abhorrent behaviour will cease over time.

So this is my story, and while it’s a story of terrible destruction, it’s also a story of redemption and salvation. A story that illustrates how with appropriate help, even the most grievously wounded people can rise above adversity and change their lives for the better. In my case that vital help came from my wife and family, my friends and the driven medical professionals who helped me back from the brink. I would never have been able to do this without their bedrock support.

My sole aim is to be happy, be useful, cherish my family and friends and help anyone in need of support and continue to back Bravehearts when and where I can.

This is a quote from The Royal Commission:

“Violators cannot live with the truth, survivors cannot live without it. There are those who still, once again are poised to invalidate and deny us. If we don’t assert the truth, it may again be relegated to fantasy, but the truth won’t go away. It will keep surfacing until it is recognised. Truth will outlast any campaign mounted against it, no matter which generation is willing to face it and in so doing protect the future generations from such abuse.”

Do you want to share your story?

Sharing your own story of survival can be a powerful way to help other survivors of child sexual abuse feel like they aren’t alone in their journey. Many survivors also feel sharing has helped them find hope and healing. If sharing your story is something you are interested in, please reach out to us using the form at the end of our dedicated Survivor Stories page.

BACK

BACK